Ben Kelly reflects on the superstar’s life with those who witnessed one of the greatest live performances of all time

13 July 1985 was Live Aid – The Day The Music Changed The World, The Global Jukebox.

Bob Geldof’s grand plan, conceived as the main course to the entree of the Band-Aid single from Christmas 1984. The concept was far from simple: two concerts, in London and Philadelphia, with every major pop star on the planet, before the eyes of the world, to gather the donations of millions, all for the famine-struck people of Ethiopia.

Almost 40 years later, multiple line-up concerts, cross-continent events and global telethons are nothing new, but in 1985, the world had never seen anything like it.

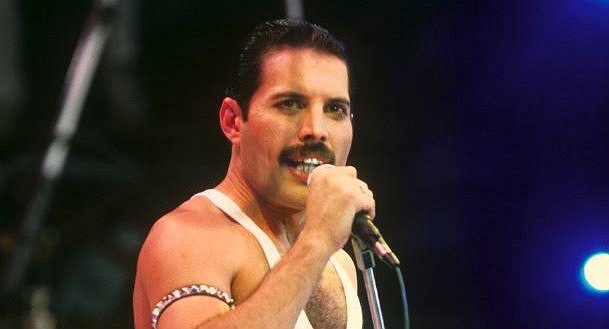

And, of all the memorable moments the day created – Bono leaping into the audience, Phil Collins playing both shows with the help of Concorde, and the rousing showstopper from Tina Turner and Mick Jagger – the most iconic moment of all was undoubtedly delivered by Queen, and a masterful, career-defining performance from Freddie Mercury.

When it came to organising Live Aid, Queen was high on Bob Geldof’s hit list, but the band weren’t immediately won over.

Lesley Ann Jones is the author of Freddie Mercury: The Definitive Biography, who went on the road with the band many times and covered Live Aid. She told me Freddie had been slightly miffed at not being invited to record Do They Know It’s Christmas? the previous November, and had to be asked extra nicely by Geldof to perform at Live Aid.

“Eventually Bob called up Queen’s manager and said ‘Look, what’s up with the old queen? It’s the perfect stage for him. It’s the entire world’. When it was put to him that way, Freddie just got it, and said OK, because it couldn’t happen without him. It was very much Freddie’s day.”

The band were renowned for their live performances – having just performed for 325,000 people at Rock In Rio earlier that year – but they were still on the verge of being a bit past it.

“Nobody knew at the time, but Queen were very much on the wane at this point”, Lesley Ann says. “Things weren’t going that well.”

Their 1984 effort The Works hadn’t been a huge hit, and Freddie had just released his solo debut in April 1985, Mr Bad Guy, an implication that the band was on something of a break. 15 years into their career, and they were looking like more of a heritage act than a serious contemporary force.

Nevertheless, they were guaranteed to deliver the kind of showmanship Geldof was determined to deliver. Paul Gambaccini was one of the BBC’s big hitters who was assigned to cover Live Aid from Wembley Stadium.

“I went up to Wembley to interview the artists backstage for television and radio,” he told me.

“Freddie wouldn’t give an interview on the day because he had vocal trouble. His doctor told him not to do the show, but of course he was determined to do it anyway.” Gambaccini and Mercury were friends, but even he didn’t see Queen’s magic moment coming.

“At the time you thought, ‘Who’s going to be the hottest?’ Obviously, U2 and Phil Collins were really hot. And of course, Paul McCartney was going to be on the show, so I don’t think anybody saw that the number one would be Queen. Everybody knew Queen put on a great show and would be really good.

“Nobody knew they would throw anybody else in the shadow.”

Weeks of excitement, stress and uncertainty came to a grand climax as Live Aid kicked off at 12 noon on that sweltering hot July Saturday. With a brass fanfare from the Coldstream Guards, and the arrival of Prince Charles and Princess Diana, Geldof’s concept came together spectacularly for a global audience across 150 countries.

Backstage, however, was chaotic. A sign told the stars to check their egos at the door, and dressing rooms had to be shared – as did just three press passes, which were switched between dozens of journalists waiting patiently outside.

It seems suitable that on a day that defined the ’80s, most attendees recall cocaine was in abundance behind the scenes. Freddie Mercury didn’t arrive until about 5 pm, with his Irish boyfriend Jim Hutton. He was nervous but being his usual self, and was seen downing a couple of vodka tonics. Bono has said he hadn’t realised quite how camp Freddie was until he had him pinned up against a wall, complimenting him on his singing.

Later, upon encountering David Bowie, looking immaculate in a powder blue suit, Freddie purred, “If I didn’t know you any better I’d have to eat you.”

It was 6.41 pm in London when Queen strode out on stage; Freddie punching the air, egging on the crowd before the first note of music was even played. They were the last act to perform in daylight, which Roger Taylor told me was very odd for them.

“Lights are everything, but they do nothing in the daytime. We never performed in the daytime.” But, he says, their hands weren’t forced.

“We didn’t want to go on too late because we knew it would be a very long day.”

The tea time slot not only caught most of Britain sitting down for the evening, but the U.S. audience had also just joined in.

“We had only been added to the bill quite late on, and the audience was not a Queen audience, so we were nervous,” Taylor concludes.

“We knew it was going to be a big deal within the context of the day because we knew it was going to be something special, but we didn’t have any great expectations of our performance.”

Sitting down at the piano, Freddie teased the crowd with a few bashed-out chords on the black grand piano before delivering the opening ballad segment of Bohemian Rhapsody, immediately setting the tone for the mother of all sing-a-longs.

Just before slipping into the operatic section, the band simmered, and Freddie arose from the piano, fist in the air, before being handed his famous bottomless microphone stand.

With a theatrical turn, he proceeded to prance across the stage as the opening riffs of Radio Ga Ga struck up. Within seconds, the microphone was being used as a sceptre, an air guitar, and a phallic extension.

Watching back, it’s clear from this moment that he has the audience eating out of his hand, and he knows it. As he sings of “the girls and boys/who just don’t know and just don’t care,” the girls and boys of the audience – sweating and soaked from stewards’ hoses – punch the air in total unison with him.

Paul Gambaccini was backstage with the other artists in the green room, and his most clear memory of the day is their reactions.

“Everyone looked up at the monitor and you could see it dawning on them… Queen was stealing the show.”

Without even instructing them to do so, the 72,000-strong crowd spontaneously performed the now-famous overhead clap through the chorus of Radio Ga Ga – first seen in the music video for the song the previous year.

After a day of many acts who could never have dreamed of playing anywhere bigger than a regional arena, here was a stadium-worthy moment – the very kind Geldof was desperate to see – and according to some, the sight that led him to make his famous ‘Give us your fucking money outburst, when he realised they still weren’t generating enough donations.

The sight delivered an iconic image; a sea of people, completely engaged, totally enthralled by one man: Freddie Mercury.

Curiously, for someone with such stage presence, Freddie was a vastly different person in real life.

“He had a way of pumping himself up,” Taylor remembers. “He became a different person when he went on stage, and all of sudden he was magnetic, and the crowd loved it. He really was spectacular on that day.”

Lesley Ann describes the transformation she watched him undertake at multiple gigs.

“When he was offstage, he was a very low-key bloke. He didn’t even draw attention to himself, he had a quiet voice. He wasn’t a mincing queen or flamboyant. The minute he went out on stage he seemed to double in size, and he suddenly became a gigantic rock star.”

Just when it seemed like it couldn’t get any better, Freddie took it up a notch. Standing centre stage, now super inflated, he launched into his ‘Ay-oh!’ call and response. The audience mimicked him (to the best of their abilities), and the moment again reflected the interactive mood of the day.

Unlike many of the other artists, who were busy pretending that there weren’t quite so many people watching them, Freddie was determined to reach every single person watching.

During Hammer To Fall, he took a BBC cameraman by the waist, and danced with him, while looking straight down his camera, to a global audience that was anywhere between 1 and 2 billion people, tuned in through about 95% of the world’s television sets.

Sonically, if Queen sounded a hell of a lot better than all the other acts, it was because they’d given themselves a sneaky leg up in the audio department.

Lesley Ann was watching from the side of the stage, and shed some light on the technical side of things.

“Queen had their sound engineer go out the front to ‘check the system’, but what he was really doing was whacking up the sound level, so Queen was actually producing a sound on the day that was much louder than all the other bands that had come before. So of course people stood up and took notice.”

Freddie strapped on guitar for Crazy Little Thing Called Love, and spoke his only words of the whole set.

“This next song is only dedicated to beautiful people here tonight. It means all of you,” he grinned, “thank you for coming along, and making this a great occasion.”

When Roger Taylor dropped the famous drum riff of We Will Rock You, things reached fever pitch, and to close out, Freddie led the audience, swaying en masse, through a rousing We Are The Champions.

By the time he blew the crowd a farewell kiss, they were screaming in a sort of rock music ecstasy, and he was drenched in sweat – looking positively post-coital.

As the other members of Queen took modest bows and left the stage, a sunset was cast across Wembley Stadium, but it didn’t reflect any sort of diminution for the band. It rather implied the light left with Freddie, and a little extra luck was needed for the following acts to shine – even though that did include David Bowie, The Who, Elton John and Paul McCartney.

”Queen were slightly past their peak when they went on,” concludes Paul Gambaccini, “When they came off they were at a new peak.”

Whether or not Queen realised it, they had not only delivered the performance of the day, not just the performance of their careers but possibly the greatest live performance of all time. Certainly, that was the consensus reached by a 2005 BBC poll of 60 journalists and music industry experts.

When I put it to Roger Taylor, he’s all too modest.

“Oh stop. Who decides this? Did they go to every single gig?!” He feels the atmosphere of the day contributed hugely to the electricity of the moment.

“You couldn’t fail,” he says, “But you could fail to do it spectacularly!” On Freddie, Taylor hasn’t a bad word to say (“Well we never fell out,” he shrugs), and claims the rest of the band adored him as much as the rest of the world.

Looking back though, he admits, “We didn’t fully appreciate how incredible Freddie was until we lost him.”

Freddie was 38 when he entertained the world at Live Aid, and while it was undoubtedly the peak of his career, it also marked the beginning of the end of his short life. Just a year before he was diagnosed with HIV, it’s likely that Freddie knew – on some level – that he had already contracted the virus.

“I can’t say for sure that he knew on the day, he never told me that,” Lesley Ann says, “but Barbara Valentin – an actress who he lived with in Munich at the time – recounted a few experiences to me of Freddie cutting himself in the bathroom and screaming at her to stay away from him, so it seems likely that he knew at that point.”

Beneath the bravado of the Live Aid performance, Freddie was now harbouring two huge secrets about his personal life.

Famously private, Freddie never publicly admitted to being gay, and most people were entirely unaware. Curiously, the ‘Castro clone’ image he presented to the world was hugely popular on the underground gay scene, but as yet entirely unknown to the general public.

His physique and moustache were seen by many as being strong indicators of his red-blooded, hetero masculinity, and his theatricality was simply that; he was, after all a performer.

It’s hard to watch back the Live Aid performance and not see an alpha gay in his element, but in 1985, that was not how it was perceived.

“The majority of the audience watching Live Aid would not have been aware he was gay,” Paul Gambaccini confirmed, simply citing a more innocent contemporary attitude.

“They only thought that people were gay if they said they were gay.”

When Freddie was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, the information was not shared with anyone beyond the band.

“He was tested in 1986 but no announcement was ever made, every rumour was denied,” explains Lesley Ann.

Freddie was hounded for years by the press – The Sun in particular – who profiled his increasingly gaunt appearance and attempted to call him out on the true state of his health. Freddie maintained this privacy until the very end, only releasing a statement confirming he had AIDS the day before he died on 24 November 1991, aged 45.

“He was keeping his personal life private because of his parents and other members of his family,” Lesley Ann continues. “Homosexuality is not permissible in their religion. It seems awful to me now that he was forced to conceal his true identity and hide his real self for the sake of other people’s feelings. I know that he wasn’t happy. He wasn’t happy most of his life.”

Although Freddie did have an on-off relationship with Jim Hutton until his death, Lesley Ann still feels his private life was one carried out under a blot of sadness.

“His mum’s favourite song of his is Somebody To Love and that was really the song that summed Freddie up. He never really found the true love of his life.”

Had he lived, Freddie would be in his seventies, and it’s mind-boggling to imagine him alive and kicking in 21st century Britain.

“I sometimes think that he would love this,” Paul Gambaccini tells me, as we discuss the immortality Freddie enjoys.

“He would love the fact that he’s current even though he’s been dead for years. Obviously, he deserved a longer life, but nonetheless, because of the history, he does have a long-lived life.”

Financially, the success of Live Aid has long been disputed, with many claiming not enough of the £150 million raised went to the people who needed it.

Nevertheless, it invigorated the concept of musicians using their talent and profile to highlight charitable causes. Technologically though, Live Aid was an unbelievable triumph.

Happening in a world without the Internet or mobile phones, messages were sent on fax machines, every phone donation had to be answered by an actual human being, TV was analogue and there were only 4 channels.

Between sets, the artists had just minutes to switch over their equipment on a revolving stage covered in snaking wires, multiple extension leads and bulky BBC TV cameras. It was a health and safety nightmare, and a total mind fuck for anyone behind one of the dozens of control panels. The fact that the show ran for 16 hours without the whole screen going black at any point is nothing short of a miracle.

“Live Aid should not have been possible,” says Lesley Ann. “It was old-fashioned and archaic. Somehow or other, it came together on the day. But with the birth of digital technology, that kind of thing was no longer an amazing feat.”

Likewise, never again could a performer hope to be given a global platform quite like it, let alone the opportunity to seize it as Freddie did. There has never since been an event with as many viewers, evoking as much heightened emotion, all engaging in One Vision (a song Queen wrote about the event), and – because of the way we now consume television in the digital age – there never will be again.

Live Aid brought the world together, and everyone shared the moment, at the moment.

It just so happened to be Freddie’s finest moment too – a moment in the gay community’s history when one of our greatest heroes represented us at our absolute best – even if it was from within the closet.

Watching it back on YouTube, Freddie’s energy and spirit appear as symbolic of the gay community. In the face of adversity, he puffed up his chest and battled onward – not just to entertain people, but to totally electrify them.

All too often in the gay community, we idolise tragic heroism in our much loved female stars; perhaps the ultimate instance came from within our own ranks.