Squeal for me, piglet,” I said. “Want me to feed you your food?” ¶ The voice on the other end of the phone moaned. ¶ “You want to get fat for your master, little piggy?” I continued. “You like that? Now oink for me. Tell me how much you love your owner.” ¶ It was 2006, and this was my first job in Los Angeles, as a phone-sex operator. It wasn’t how I had planned on making it in Hollywood, but it wasn’t a bad start — to be 18 years old, new in town, and earning enough money to pay my bills. I dipped in and out of dinners, shops, and meetings to take my calls. Standing on Santa Monica Boulevard outside a CVS, I growled into my cell phone to a caller, “You want me to fatten you up like livestock getting ready for slaughter?” I kept it up as passersby eyed me strangely. “Time for your Geritol.”

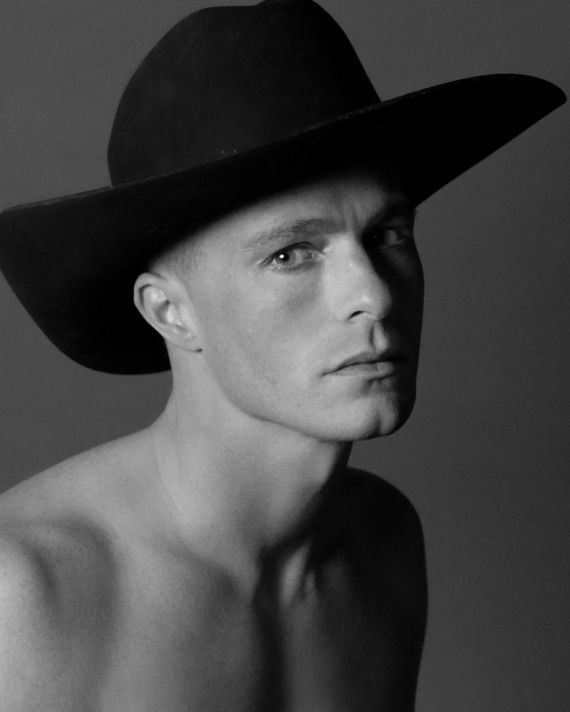

I could never understand why so many of these guys had a thing for farm play. But I could sell a farm scene: I was from the Midwest, a little town in Kansas called Andale, northwest of Wichita. I thought it was weird that my phone-operator job had nothing to do with the way I looked since that was the only thing about me that had ever been affirmed — mostly by much older men. My first serious relationship, if you could call it that, at 14, was with a man in his 40s who worked in the area. I began go-go dancing at a gay bar in Wichita that same year — fake ID in hand — after sneaking in one night with a few castmates from my community-theater program. I felt at home there. The thumping of the beat rattled the club, and from up on the box, all the men looked like wild animals. We danced in cowboy hats, low-rise boot-cut jeans, and no underwear, sweat trickling down our abdomens toward our shaved crotches.

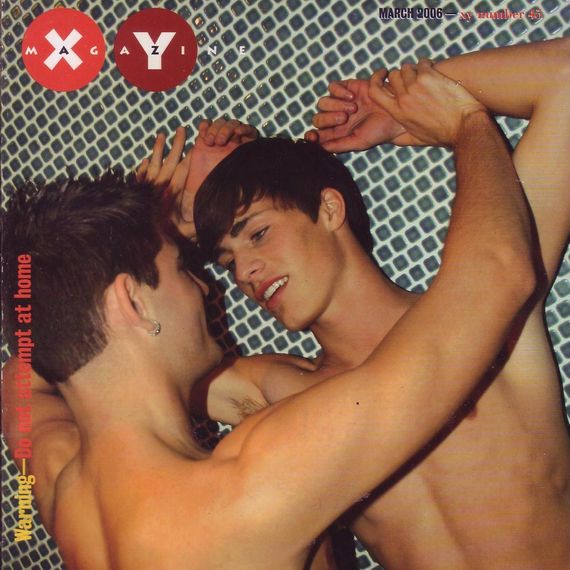

By age 15, I got my first modeling agent. I had submitted photos to the top agencies in New York hoping they’d be my ticket out of my provincial hometown. When I got a message on Myspace in 2005 asking if my then-boyfriend, Jay, and I would pose for a gay magazine called XY, I didn’t think twice. As soon as I got there, I knew exactly what to do. I took my shirt off. I changed into a pair of shredded jeans. I began lifting dumbbells. I put a beanie on and stuck my tongue out. I looked up at the camera, trying to fuck it the way I’d seen boys do in other shoots. I crawled on my knees, changed into a pair of pants with a hole in the crotch, and lay on the bed shirtless with my legs spread so you could see my white underwear through the rip in the groin. Everything but the camera fell away. It felt just like dancing at the club.

Jay and I were invited out to Los Angeles to celebrate the release of the issue. During our trip, we wound up at the home of a movie executive who lived in a mansion in the Hollywood Hills. There were lots of other young men there, milling around the cavernous living room. They all looked like me: wide-eyed and full of promise. At dinner, I was seated next to a writer. He was 50ish and had a familiar hunger in his eyes. “So you’re moving out here, right?” he said. “Yes!” I replied. “With Jay, my boyfriend — he’s right over there.” “Ah, young love,” he said. “That’ll end. When it does, give me a call. I can help you if you need anything.”

After I returned home, I received a package from the writer. He had gotten my address from a mutual friend. It contained some calling cards — I had lied and told him I was out of minutes for my cell phone when he’d asked for my number — and an expensive calculator because I’d mentioned I wasn’t doing well in math class. I found his gifts to be encouraging. If all I have to do is bat my eyes and flirt with people to get opportunities in Hollywood, I thought, that’s already what I do all the time. It was the most obvious thing in the world to me.

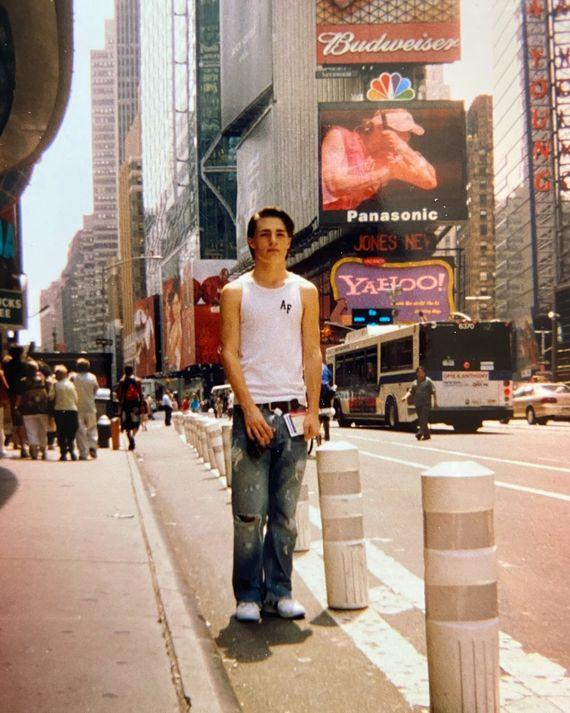

Haynes, 18, photographed by a friend soon after his move to L.A. Photo: Paul Jasmin

I moved to L.A. after high-school graduation. After one year of phone-sex work and unanswered submissions to every acting agent or manager I could find online, I was starting to question why I had come. Finally, in 2007, a management company took the bait. “We love your look,” a rep said over email. Later that week, I visited the office for a meeting. There were two teenage boys roughhousing in the lobby. Through a window, I could see a tiny pool in which guys in swim trunks were splashing and laughing. It was disconcerting. I imagined all of them leaving their hometowns to come here and find they would be competing with so many others who looked just like them.

Eventually, I was called upstairs to the office, where one of the owners of the company — let’s call him Brad — was waiting for me with his assistant. He was wearing a skintight muscle tee and had gleaming-white veneers. He was middle-aged, and his hairline looked as if it had recently been rejuvenated.

“How did you find out about us?” he asked.

“I found you online,” I said. “You know the actors on the WB? I want a career like that.”

“Why are you using your hands so much when you talk? And your posture is too … loose,” he said. “We’re definitely going to have to change your mannerisms. They’re a little too … theater.” Code for gay. I stood up straighter. “Can you sing?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said. I began singing “Home,” from the Broadway musical Beauty and the Beast. After a few beats, he stopped me.

“Do you have a new headshot?” he asked.

I handed him one of my comp cards from the modeling agency, which was all I had. He studied it. Suddenly, I didn’t want to be there. “I’ve seen enough,” he said. “You should come to acting class tonight. I’d like to represent you.” That was it. After months of waiting, it felt too easy. And confusing. Did he like my performance or just my looks? And was he also my acting coach?

In class, there were about 20 other young actors. Brad set us up in twos: some pairs of men, some of women, others mixed. I was paired with a good-looking guy I’ll call Ethan, whom I recognized from a popular television show.

“Today you’ll be working through the scenes we’ll be putting on in Thursday’s class,” Brad said. “First, we’ll have you cold read on-camera.”

Ethan rolled his eyes. “Sexy-scene night,” he said.

“What?” I asked.

“Thursdays are sexy-scene night,” he said with a grimace. When it came time for me to read the scene, my hands were shaking. It was from The War Boys, a low-budget film about two young men who fall in love while living in a border town. I became so aware of my mannerisms I could hardly get a word out of my mouth.

“Stop moving your face so much!” Brad yelled from a seat in the front row. “Not so musical theater!” He stopped me. “You need more practice,” he said. “You and Ethan take some time over the next couple days to get ready for Thursday’s class.” Ethan looked at me disdainfully. I mouthed “Sorry” to him.

The next day, I met Ethan at his apartment, where he was rooming with a few other young actors, all of whom seemed straight and uninterested in befriending me.

“We’re going to have to get really comfortable with each other if we’re going to do this during sexy-scene night,” Ethan said as we began reading together.

“What’s sexy-scene night?” I finally asked.

“We all do sex scenes where we have to get fully naked,” he said. “It teaches us how to be comfortable showing our bodies onscreen.”

“We’re doing this scene naked?”

“Yes.”

“We’re doing a sex scene?”

“We don’t actually have sex,” he said. “But according to this stage direction” — he flicked through the pages — “I’ll be mounting you and thrusting in and out of you. And we have to make out. So why don’t we get it out of the way and make out now? So we’re both comfortable.” I must have looked confused. “I’m straight,” he added. “Just so you know.” Ethan grabbed me by the back of my head and kissed me for longer than I was expecting. Our lips pressed together. He gazed into my eyes with such tenderness it confused me. Were we about to actually have sex? Or was this acting? Then his eyes went cold. “Okay,” he said, “let’s run the scene.”

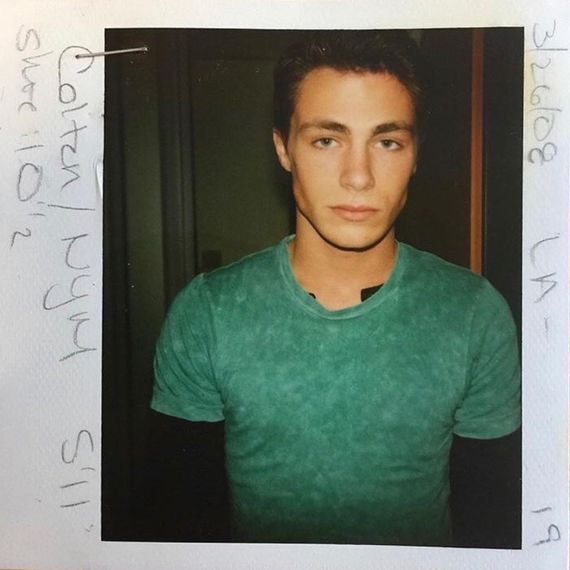

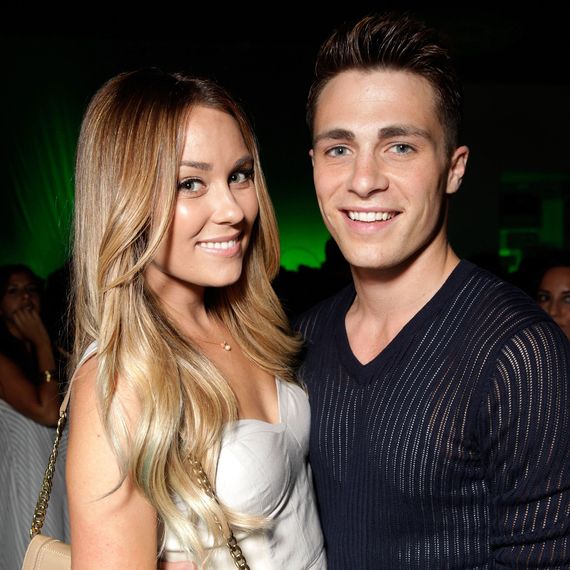

Clockwise from top left: 2006: Haynes’s photoshoot appears in the gay men’s magazine XY. He says his Hollywood team later tried to suppress the images. 2007: At the Vogue offices in New York during his modeling years. 2011: Haynes played the jockish Jackson Whittemore on Teen Wolf. Holland Roden (right) played his girlfriend. 2011: With Lauren Conrad. He says he was encouraged not to deny rumors that they were in a romantic relationship. Photo: XY magazine (magazine cover); Courtesy of Colton Haynes (polaroid); MGM (Teen Wolf); Todd Williamson/Getty Images (Conrad).

Up first that Thursday night was an actress and actor re-creating Halle Berry’s sex scene from Monster’s Ball. “Make me feel good,” the young woman said, tears streaming down her face. She took off her lacy tank top and revealed her breasts. “I just want you to make me feel good.” She hiked up her skirt and pulled her underwear down to her ankles over her stripper heels.

The young actor playing the Billy Bob Thornton part was already on a hit TV show. I watched, paralyzed, as he unbuttoned his pants, stripped naked, and crawled behind her on his knees. Mascara tears ran down her face. She stared at us, at Brad. As her scene partner took her from behind, she let out a bloodcurdling scream, as if he had really just jammed himself inside her. “Make me feel good!” she screamed. “Make me feel good!” It was disturbing: a young woman pretending to be penetrated in front of a class of actors for the sake of impressing her manager. I was terrified knowing Ethan and I would be performing next.

We began with our lines. Eventually, I had to take off my pants. I stared into Ethan’s eyes, feeling everyone else’s eyes on my body. I pulled down my boxers, and I got on my knees. I turned Ethan, bare naked, toward the audience and began performing a fake oral-sex scene on him. Then he threw me down on all fours and simulated penetration while my dick flapped back and forth, slapping against my stomach. I closed my eyes so I wouldn’t have to look at the audience.

After it was over, we put our clothes back on and stood onstage while Brad critiqued us. “Your balls hang so low,” he marveled to Ethan.

“Thank you,” Ethan said.

Then Brad’s gaze turned to me. “Colton, we have got to cut that hair,” he said. “And please stop moving your forehead so much. It looks like I could grow crops in those lines. We’ve been over this already.” Of all the things that had happened to me in my life, I had never felt more demoralized.

Later that week, Brad arranged for me to meet a hairstylist at his house. He presented this opportunity like it was a favor, so I pretended to be grateful as the man sheared my hair military short. Brad had just finished working out with his trainer, and there were still beads of sweat on his Botoxed forehead. He was eating a bowl of cereal; milk dribbled down his chin as he appraised my new hair. “There’s the boy everyone will want to see,” he said. “There’s the star.” I felt naked again. I couldn’t hide behind my mop of tween-star hair anymore.If all I have to do is bat my eyes and flirt with people to get opportunities in Hollywood, I thought, that’s already what I do all the time.

In our next on-camera class, Brad praised me. “Everyone needs to look at Colton,” he said. “This kid is going places.” I knew what he was doing: withholding validation, then meting it out one morsel at a time so you craved the attention even as you hated him for being stingy with it. It was the kind of behavior that bonded him to the damaged young people who passed through his class. I was happy he had said my performance was strong — as though I had passed the test. People with a stronger sense of self-worth might have quit after being so humiliated, but I belonged here. I guess I was an actor after all.

Brad suggested I start working in his office to familiarize myself with the business. I sat at a desk and submitted his clients — my classmates — for TV and film roles on a casting-submission site called Breakdown Express. There wasn’t any pay, but he promised that if I did this, he would get me an agent. A few months later, he called me into his office after class let out.

“You might be ready to meet with agents,” he said. “The one I want to place you with isn’t interested, so let’s get him interested. Tomorrow on your lunch break, I want you to deliver some paperwork I owe him. You’re going to deliver it in a cowboy hat and an unbuttoned western shirt.”

I actually did it — I unbuttoned my shirt in the elevator and walked through the packed waiting area, past rows of assistants. Judging by the look on the agent’s face after I delivered him the package, I thought it might have worked. The next day, I was summoned into Brad’s office. I thought this would be the moment he told me I had my first agent.

“Colton, he still isn’t interested,” Brad said flatly. “I’m sorry, but this isn’t working out. Your voice, your mannerisms — they’re still too … gay.” I looked at him incredulously.

“You still have so much work to do. We think you will be better served at a different management company,” he said.

I felt tears trickling down my cheeks. I wiped them away, furious this man was making me cry. “What am I gonna do?” I asked.

“If you’re hard up for money,” he said, “I know a place that might be able to help.” He wrote down something on a business card, then handed it to me. “It’s been a pleasure working with you,” he said. Back at my apartment, I looked at the card. On the back, he’d written “rentboy.com.” I typed it into my browser. It was a site for sex workers.

2015: As superhero Roy Harper on Arrow. He initially left the show after season three for mental- and physical health reasons. 2017: As Detective Jack Samuels on American Horror Story: Cult — one of the rare roles he booked after coming out. 2021: A self-portrait was taken in Haynes’s home studio. Photo: Warner Bros. (Arrow); TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy Stock Photo (American Horror Story); Courtesy of Colton Haynes (self-portrait).

Maybe you’re thinking, So what? Boo-hoo. What did I expect — to be handed a satisfying career because of the way I looked? Now I can see I was foolish to think making it would be easy or fun. The thing that made me valuable in private — my conspicuously gay sexuality — was a liability as I tried to make my way through the industry. This was in an era when casual homophobia was still a regular punch line on TV sitcoms. Modern Family wouldn’t premiere until a few years after I arrived in L.A. Actors had only begun to come out publicly, and none of them looked like the straight romantic lead. There are still few gay leading men in Hollywood who are out of the closet. So I did what I was told to do. I took lessons with a voice instructor who had me talk while holding a highlighter between my teeth for the entire class so that when I took it out, my diction was crisp and clear. I practiced speaking with a folded Post-it note under my tongue to teach me to make my S sounds less sibilant since the softness of them made me sound gay. Within a few weeks of being dropped by Brad, after cold-calling casting offices and messengering my headshot around town, I booked my first role in an episode of CSI: Miami. The day after it aired, calls started pouring in from companies wanting to represent me.

I signed with a new team, but the rules were the same. It considered the XY photoshoot I had done so radioactively it had lawyers send cease-and-desist letters to anyone who posted the images online. When I was photographed cozying up with Lauren Conrad at an event in 2011, I was told not to deny our rumored relationship — better to have the tabloids speculate about us. (She must have known I was gay, but we never spoke about it.) At a photoshoot for a fashion editorial, the XY pictures were up on the mood board. A member of my team threw a fit. I understood because it was explained to me repeatedly — by managers, agents, publicists, executives, producers — that the only thing standing between me and the career I wanted was that I was gay. It was like this for my best years of work, throughout the early 2010s, as I built a career on young-adult shows like MTV’s Teen Wolf and the CW superhero series Arrow. It’s not just straight people who are the gatekeepers — the call often comes from inside the house. I’m eternally grateful to the handful of gay men who created opportunities for me: Jeff Davis, Greg Berlanti, and Ryan Murphy. They were the exception, not the rule.

My mental health deteriorated, and I grew dependent on alcohol and pills. When a doctor suggested my secret was making me sick, I knew he was right. I came out of the closet in an interview with Entertainment Weekly in 2016. I hoped it would set me free, and in some ways it did. An outpouring of support followed. But people also published think pieces saying it had taken me too long; another gay actor implied the way I’d done it was cowardly. And incidentally, the work mostly dried up. When I was closeted, I beat out straight guys to play straight roles, and I played them well. Now, the only auditions I get are for gay characters, which remain sparse. Is that because I’m not very good? Maybe. But that didn’t stop me from booking roles before. It’s no different for the young gay actors I see coming up today, trying to make it in a system that isn’t built for them.

To be a gay actor in Hollywood, even in 2021, is to be inundated with mixed messages: Consumers are mostly straight, so don’t alienate them. But lots of the decision-makers are gay, so play that game! Now that I’m older and sober, I’m trying to square who I am with the inauthentic version of myself I invested in for years. I often wonder how different things would’ve been if

I were allowed to be who I was when I moved to town: a hopeful kid confident in his sexuality.

I saw Brad again a few years after he dropped me. I was at an industry event, and he was sitting at my table along with the actress who had played the Halle Berry character on sexy-scene night. He was still her manager. We locked eyes across the table but didn’t say hello. Later in the night, he came to my side of the table and said quietly to me, “Dropping you was a mistake.”

It should have validated me. Maybe at the time it did. Now I’m not so sure. On some level, he had been right: I was too gay. He’d understood something I hadn’t at the time, which was that all of this, everything in Hollywood, was about selling a fantasy; you just had to know who was buying.